Spectrum-related tensions reemerged during a workshop on Thursday (March 12, 2015) organized to gather feedback on a testing plan to help protect GPS receivers.

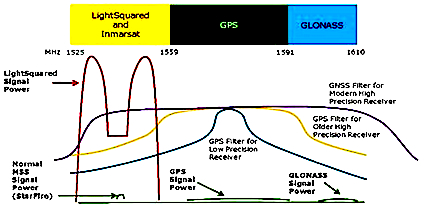

The plan is part of the GPS Adjacent-Band Compatibility (ABC) assessment — a wide-ranging effort to determine the power levels at which services operating in frequencies next those used by GPS and other GNSS systems can broadcast signals without causing interference to GPS signals.

Spectrum-related tensions reemerged during a workshop on Thursday (March 12, 2015) organized to gather feedback on a testing plan to help protect GPS receivers.

The plan is part of the GPS Adjacent-Band Compatibility (ABC) assessment — a wide-ranging effort to determine the power levels at which services operating in frequencies next those used by GPS and other GNSS systems can broadcast signals without causing interference to GPS signals.

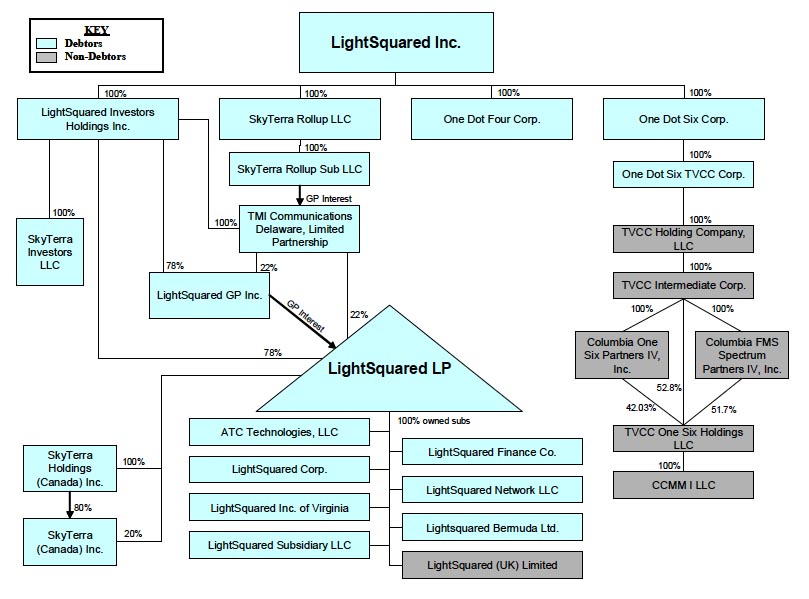

The study was proposed in February 2012 after the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) reversed course on a request from Virginia-based LightSquared Inc. to reallocate satellite spectrum for a ground-based broadband network, which an extensive test campaign demonstrated would overload most types of GPS receivers. LightSquared later declared bankruptcy.

The two-stage test plan described during the workshop held at the Aerospace Corporation in El Segundo, California, would first evaluate a wide range of current GPS receivers and then future receivers to provide the data to create a “mask” that maps out the safe power levels at different frequencies. The U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) is leading the effort, which conducted an initial ABC workshop last September at DoT’s John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Under the current schedule the DoT team plans to finalize testing requirements by the end of this month and complete the test plan by April 30, followed by publication in the Federal Register. The official notice for comment is expected by around May 5 with comments due some three weeks later. The DoT team will consider the comments and finalize the plan with testing to begin this summer. They want to identify which receivers need to be tested by the end of May.

Although the government still has the LightSquared plan on hold, the pressure being applied by the White House to find more spectrum for the broadband community was reflected in opening comments by Jim Horejsi, the chief engineer at the Global Positioning Systems Directorate at Los Angeles Air Force Base.

“[F]undamentally there are two considerations that you have to take into account,” Horejsi told workshop attendees. “First and foremost, find spectrum for broadband mobile applications — that’s the goal. But do it in such a way that we protect the GPS users to a reasonable fashion. So, I suspect most of the discussion previously and today will circle around ‘reasonable.’ So that’s your job here, to figure that out and sort through that.”

Having the meeting as a workshop, Horejsi said, was to “make sure that things are brought into the open so that discussion can happen.”

To ensure openness and transparency, the Volpe Center’s Steve MacKey said the government is now proposing to sponsor the testing at a separate facility such as White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, as opposed to having the manufacturers conduct the tests based on an agreed test methodology. DoT’s Volpe Center is supporting the receiver evaluation.

The assessment team walked through a number of test parameters for receivers in seven categories: aviation (noncertified), cellular, general location and navigation, high precision, timing, networks, and space-based. They also solicited feedback on where those receivers are used — specifically dense urban, urban, suburban, rural, or space environments — and the needs they supported including uses such as earthquake prediction agriculture emergency response and national security. The team asked about testing for intermodulation effects and capturing data beyond the signal-to-noise ratio like time, carrier phase, pseudo-range and cycle slips.

Feedback during the discussion appeared to help the team decide to use radiated testing with preliminary, “wired” laboratory simulation for test development and validation. Final decisions on these and a wide variety of other factors will be presented in the draft plan when it becomes available for comment. The presentation slides with the team’s questions should be posted in a few weeks. Material should be found most easily at <http://www.gps.gov/spectrum/ABC>.

LightSquared Turns Up the Heat

Test parameters proposed in an afternoon presentation at the workshop by Geoff Stearn, vice-president for spectrum development at LightSquared, triggered heated debate.

Stearn suggested that a smaller swath of frequencies be tested and that the testing be designed to inform the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which he described as the regulators, to consider “the economic and social interest — the public interest.”

GPS receiver manufacturers should supply, he said, sales figures to help support a selection of receivers that would have to include the top 10 selling models in the United States for calendar year 2014. The tests would not be limited to these models, Stearn suggested, but should definitely include them.

The LightSquared test proposal continued by recommending that DoT the results to create a series of receiver masks, including one that illustrates the impact of adjacent band interference on all the receivers in a category, another that eliminates the 15 percent of receivers with the poorest rejection of the adjacent band signals, and yet another with the top 50 percent of such receivers.

The company also wanted a complete set of data with the names of the manufacturers of each receiver — a change in the confidentiality arrangements that governed tests done several years ago when the LightSquared proposal first was being considered. Furthermore, the test results should indicate receiver resiliency and that should be made public.

“Users of GPS have a keen interest,” Stearn said “in knowing whether their devices are adequately protected from the adjacent band.”

The focus of the assessment, he asserted, should be positioning and timing error, not the carrier-to-noise ratio, which “just is not a good proxy for harmful interference” — an assertion with which many at the workshop disagreed.

Stearn also asserted that the FCC “had exclusive jurisdiction to regulate spectrum emissions.” The FCC was widely seen, during the initial policy debate in 2011, as supporting LightSquared.

“It’s really unprecedented for an agency to go outside of the established process,” he said, “because typically they would ask the FCC to conduct such studies on their own. The mere fact that we’re here today means we haven’t convinced the DoT and Volpe that that’s the proper way to go.”

The tests should provide evidence of actual harm,” Stearn said, arguing for an approach that would put the interference burden on GPS users.

“Is reduced accuracy an ‘actual harm’ in your mind?” asked another attendee.

“The FCC’s job as the regulator,” said Stearn, “is to define what harmful interference means in this context. They do that for a living.”

“Excuse me, that’s not true,” said Don Jansky, former associate administrator for the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). “That’s absolutely not true.”

“Harmful interference,” Jansky added, triggering a heated exchange with more than one LightSquared representative, “has never, as a matter of national policy, never been quantified. It is an administrative regulation both internationally and domestically. C/N0 (signal to noise) is a standard, which has been used forever. In fact, you must have a standard as a basis for doing your testing and measurement — against which to measure something.”

Which led to the following exchange:

LightSquared: I agree that “harmful interference” is not defined.

Jansky (interrupting): It’s not just not defined, it’s not quantified.

LightSquared: I’ll finish talking, and then I’ll let you respond. Harmful interference is defined in many different contexts by the FCC. So, I agree with you that it’s not defined as a numerical percentage in any one band. The FCC does define it. But the FCC’s job is to look at a particular band and define it in that context.

Jansky: I’m sorry; you are misusing the words “harmful interference.” Secondly, I have to deal with another misperception that you have. The FCC is not the final arbiter of the emissions. There is joint responsibility with NTIA. These agencies and NTIA do not report to FCC. They have a separate regulatory regime. And they have joint responsibility, particularly for the GPS band. So, they are not the final arbiter of what is the regulatory aspect regarding emissions. You should understand that. I don’t think you understand how spectrum management works in the United States.

LightSquared: I don’t want to continue the debate. I understand that that’s the NTIA’s view. The Communications Act invests the responsibility to regulate commercial enterprises, which is LightSquared, with the Federal Communications Commission.

Jansky: That may be for LightSquared, but it isn’t for the United States.

LightSquared: We’re talking about rules that would affect LightSquared.

Jansky: We’re talking about rules that would impact GPS.

Congressional Action Could Buttress LightSquared Position

Although the debate seems odd given that the current division of regulatory responsibility is fixed, ongoing moves in Congress have put the matter in flux.

Rep. Fred Upton, R-Michigan, the chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, and Rep. Greg Walden, R-Oregon, the chairman of the Communications and Technology Subcommittee, are in the process of updating the Communications Act. One of the issues they have raised is the role of the NTIA. Calling the responsibilities of the FCC and NTIA “potentially duplicative” the two sought comments last year on whether NTIA’s role should change. At least one communications industry association has suggested that NTIA be made an advisory body.

Another point raised by LightSquared points to a second emerging debate and, perhaps, a broader strategy to reopen the debate now that the Senate has changed hands and other factors have shifted.

Stearn asserted that GPS-only receivers be the only ones tested during the assessment since signals from other constellations like GLONASS were not authorized for use within the United States.

The need for authorization was raised at the PNT advisory board meeting in December. Ronald Repasi, the deputy chief of the FCC’s Office of Engineering and Technology, told the board that under existing regulations GNSS signals from international constellations had to be authorized for use in the United States. Although he did not suggest an effort would be made to block signals from constellations like GLONASS, Galileo, or Beidou, or go after owners of multi-GNSS receivers, he did say the U.S. would not protect unauthorized signals.

Limiting the test to GPS-only devices could skew or limit the results. Although the second round of testing is specifically supposed to include multi-GNSS receivers, the funding for that future effort is not set and could be undermined in Congress, particularly if the foreign GNSS system authorization issue has not been resolved.