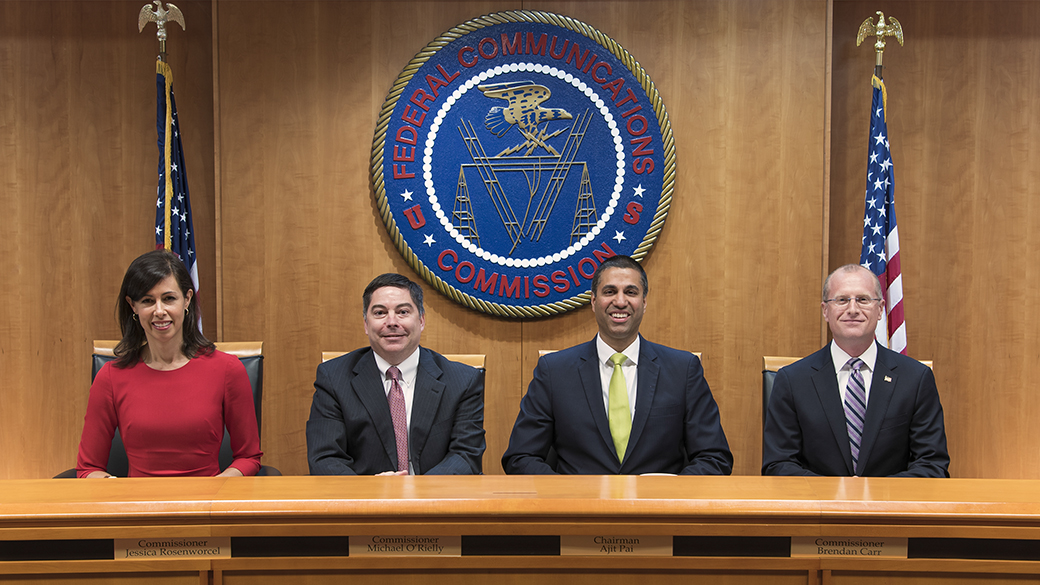

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai. Photo source: Wikimedia Commons.

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai. Photo source: Wikimedia Commons.The U.S. Congress is prepared to deliver the coup de grace to a new rule aimed at protecting the personal information — including the geolocation — of broadband internet users. The move, one of a number aimed at eliminating Obama-era regulations, would slice through months of debate, and federal regulators’ own backpedaling, to kill the pro-privacy rule in a way that makes resurrecting it extremely difficult.

The U.S. Congress is prepared to deliver the coup de grace to a new rule aimed at protecting the personal information — including the geolocation — of broadband internet users. The move, one of a number aimed at eliminating Obama-era regulations, would slice through months of debate, and federal regulators’ own backpedaling, to kill the pro-privacy rule in a way that makes resurrecting it extremely difficult.

The rule on Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services would, among other provisions, mandate consumers be given opt-in and opt-out choices for sharing their private data depending on the sensitivity of the information. For example, consumers would have to opt-in before their internet provider could share financial details, health information, Social Security numbers, the content of communications, information pertaining to children, web browsing history — and their precise geolocation data.

Crafted by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) during the Obama administration the 73-page rule was finalized and then published December 2, 2016 with some elements, including changes to the existing opt-in/out rules, set to go into effect on March 2. Parts of the rule got hung up in a required review at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and then the FCC stayed elements involving information security on March 1, pending reconsideration.

“The Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission are committed to protecting the online privacy of American consumers," said Ajit Pai, the new FCC Chairman chosen by the Trump administration, in a March 1 statement. "We believe that the best way to do that is through a comprehensive and consistent framework. After all, Americans care about the overall privacy of their information when they use the internet, and they shouldn’t have to be lawyers or engineers to figure out if their information is protected differently depending on which part of the internet holds it."

Those differences have to do with the kind of firms the rule covers. The regulation applied to the providers of broadband internet access service (BIAS) — firms like Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T — but not to their enterprise customers, say firms with websites that collect personal data. Pai said this was unfair.

“The federal government shouldn’t favor one set of companies over another — and certainly not when it comes to a marketplace as dynamic as the internet," Pai said in the March 1 statement, which was issued jointly with Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chairman Maureen Ohlhausen. "So going forward, we will work together to establish a technology-neutral privacy framework for the online world.”

The FTC had been overseeing privacy matters related to service providers but was taken off the beat in 2015 — and Pai acknowledged the concern that the stay was leaving a gap in consumer protections. The stay, he wrote, "is a step toward properly filling that gap."

"We disagreed with the FCC’s unilateral decision in 2015 to strip the FTC of its authority over broadband providers’ privacy and data security practices, removing an effective cop from the beat," he said. "The FTC has a long track record of protecting consumers’ privacy and security throughout the internet ecosystem. It did not serve consumers’ interests to abandon this longstanding, bipartisan, successful approach."

But it’s not that simple, according to the Consumerist, a publication of Consumer Reports. Putting privacy oversight back in the hands of the FTC involves reopening the highly controversial issue of net neutrality — that is the decision made by the FCC under the Obama administration not to allow internet service providers (ISPs) to charge different amounts for different types of products or otherwise favor or block content or websites.

"The FTC literally can’t enforce privacy standards for ISPs so long as those companies are defined as Title II common carriers under the law — which, thanks to our old friend net neutrality, they are," the Consumerist reported.

Congress Steps In

While the issue is complicated, lawmakers are poised with a simple answer. The week after the FCC stay was issued more than 40 lawmakers joined an effort to simply dispose of the rule.

A joint resolution to eliminate the regulation was introduced in the Senate on March 7 and in the House on March 8. If passed and signed by the president the one-sentence measure would disapprove the rule and “such rule would have no force or effect." The Senate bill (S.J.Res.34) had 23 cosponsors as of press time and H.J.Res.86 had 16 cosponsors. The power to flush new rules comes from the 1996 Congressional Review Act (CRA). Under this law Congress can overrule new regulations with a simple majority vote. Once a rule is thus repealed, the CRA also prohibits the issuing of any rule that is substantially the same.

Both bills were still in committee as of press time.

GPS Act

Interestingly, neither the House nor Senate version of the joint resolution has a single Democratic sponsor. Another bill focused on location privacy has bi-partisan support.

The GPS Act, that is the Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance Act, would make it illegal to determine, intercept or disclose the location of another person except under specific circumstances like during emergencies or if a warrant has been obtained. Violators could be fined up to $10,000 or the amount of actual damages; whichever is greater — and could be jailed for up to five years.

Rep. Jason Chaffitiz (R-Utah), chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, introduced the House version of the bill on March 6. It had four Republican and three Democratic cosponsors as of press time. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced the Senate bill Feb. 15. There were no cosponsors as of press time.

Wyden and Chaffitiz have now introduced versions of the GPS Act four times since 2011. Though hearings have been held, the Act has yet to make it out of committee.