Harbinger Capital Partners, a hedge fund controlled by Phil Falcone that acted as the primary financial backer of LightSquared, is suing the United States government over the failure of the proposed terrestrial broadband wireless network that would have broadcast in RF spectrum adjacent to GNSS L1 frequencies.

Harbinger Capital Partners, a hedge fund controlled by Phil Falcone that acted as the primary financial backer of LightSquared, is suing the United States government over the failure of the proposed terrestrial broadband wireless network that would have broadcast in RF spectrum adjacent to GNSS L1 frequencies.

The complaint, filed on Friday (July 11, 2014) in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims in Washington, D.C., asserts that Harbinger entered into a “contract” with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) whereby the firm would be allowed to purchase the company SkyTerra, in which it had a partial stake, and use its frequencies to support a new nationwide broadband network that Harbinger would pay to build.

The FCC sought, Harbinger contends, to support certain policy goals through the arrangement and set a number of terms and conditions in the agreement to support that end. Harbinger alleges the government then reneged upon the deal after Harbinger had spent almost $1.9 billion of its own funds to meet the terms.

The FCC did not respond immediately to a request for comment.

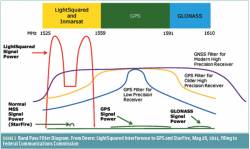

Harbinger sought permission from the FCC in 2008 to complete its ownership of SkyTerra, later renamed LightSquared, and build the network using frequencies located adjacent to those used by GPS and other GNSS systems. Tests later showed that the high-powered LightSquared signals would interfere with the operation of the vast majority of GPS receivers.

Harbinger contends the problem lies in GPS receivers that “listen in” to its spectrum and alleges the United States “permitted the GPS industry to make unlicensed and wrongful use of the spectrum in which Harbinger had invested.”

By requiring Harbinger to accommodate the GPS industry’s “continued unlawful occupation and use of LightSquared’s L-band spectrum,” the complaint states, the government “effectively reallocated LightSquared’s spectrum to the GPS industry. In other words, the United States has taken spectrum from its lawfully authorized and contractually entitled user and has awarded it to the trespasser. LightSquared eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2012. Falcone and four other directors appointed by Harbinger voluntairly resigned from the LightSquared board last month.

“The United States has breached its contractual commitment,” the firm alleges, and “has taken Harbinger’s property without just compensation.” Harbinger is seeking to recover its losses and expected profits as well as mitigation costs and “all other appropriate damages.”

Harbinger filed suit in 2013 against Garmin International and Trimble Navigation Ltd., which manufacture receivers, as well as the U.S. GPS Industry Council and the Coalition to Save Our GPS.

Is Business Plan a Contract?

The alleged contract was made public in a March 26, 2010, FCC filing. The document outlined Harbinger’s business plan to establish a wholesale, broadband network based on the company’s satellites and 36,000 terrestrial stations. Harbinger also committed not to provide L-band spectrum or network capacity to the largest or second largest provider of commercial mobile radio serves (cell phone services) and to build out fast enough to serve at least 260 million people by the end of 2015. The business plan document mentions a waiver of the FCC rules for ancillary terrestrial components (ATCs) or ground stations.

The negotiations between the parties had been kept confidential until the March release, which was linked to the FCC granting permission to Harbinger to take over SkyTerra. The FCC also granted the new owner permission to boost the power of the ground stations — which up to that point were supposed to have been ancillary to the firm’s space-based service. The distinction is important because signals traveling from satellites are far weaker when they arrive than signals from a ground station.

The decision to shift the bulk of transmissions to the terrestrial network fundamentally changed the use of the LightSquared spectrum, impacting those using neighboring frequencies. As tests later proved, receivers relying on the weak signals from the GPS satellites, which were still usable if nearby frequencies only contained satellite signals, suffered interference or were overwhelmed when subjected to the powerful ground signals planned for the LightSquared system.

The fundamental points in the lawsuit were summarized succinctly in a May 28 letter from Harbinger attorney Charles Cooper to the FCC, urging the federal agency to take immediate, positive action “to mitigate further damage to Harbinger.” The letter may explain the impetus behind a June 20 workshop on protecting GPS receivers. Notice of the workshop appeared June 2, the Monday after the letter was sent, giving potential attendees less than three weeks notice.

The GPS community was initially alarmed by the sudden rush to set up the proceeding, which appeared to be the opening of a new round in the fight — perhaps leading to an effort to set standards for receivers. The generally congenial, daylong session, however, largely rehashed old ground, leaving many in the audience puzzled. Some speculated even before word of the lawsuit circulated, that the workshop was meant to show action by the FCC on the issue in the face of earlier threats to sue.

There was action, but it was not likely what Harbinger had hoped for.

On July 1 the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), which makes decisions regarding the use of frequencies by federal agencies, sent a letter to the FCC about LightSquared’s proposed handsets and revised business plan. The letter and attached information stressed concerns about a lack of data and optimistic assumptions about interference from the handsets and how they would be used. The NTIA urged the FCC to “ensure that LightSquared’s handset proposal is adequately supported by data and a full understanding of the potential impacts on GPS receivers.”