Simple harmonic motion

Simple harmonic motionReturn to "GNSS Year in Review"

At first glance, interoperability and its implication of at least some degree of cooperation seem at odds with the idea of competing GNSS systems.

Yet the mantra of compatibility, interoperability, and even — in the terminology of GPS pioneer Brad Parkinson —interchangeability has taken on a nearly unanimous harmony in the pronouncements and deliberations of GNSS leaders.

Return to "GNSS Year in Review"

At first glance, interoperability and its implication of at least some degree of cooperation seem at odds with the idea of competing GNSS systems.

Yet the mantra of compatibility, interoperability, and even — in the terminology of GPS pioneer Brad Parkinson —interchangeability has taken on a nearly unanimous harmony in the pronouncements and deliberations of GNSS leaders.

Of course, astute businesspeople have always studied the products and marketing of their competitors in the marketplace, much as military leaders assess the composition and conduct of the forces arrayed against them. And both, when it serves their purposes, emulate aspectss of their counterparts’ efforts that appear successful, amenable, and attainable.

So, latter-day GNSS system developers have converged around many of the fundamental features introduced with the Global Positioning System — satellite/receiver trilateration, spread spectrum, CDMA, navigation message structure, and elements of signal design.

A more compelling explanation of the attention given to such matters, however, may lie in the growing awareness that all-out competition — with its exclusivity, differences, and antipathies — produces a null-sum game: forcing customers to make choices and consequently inhibiting the adoption of GNSS technology for fear of choosing wrongly. On the other hand, some greater or lesser degree of cooperation may well act synergistically to produce a larger pie that all can share.

Just as nations in the 19th century grudgingly came to the realization that agreement on a common gauge of railroad tracks would produce more trade, open and common standards in GNSS technologies can expand and expedite the growth of markets.

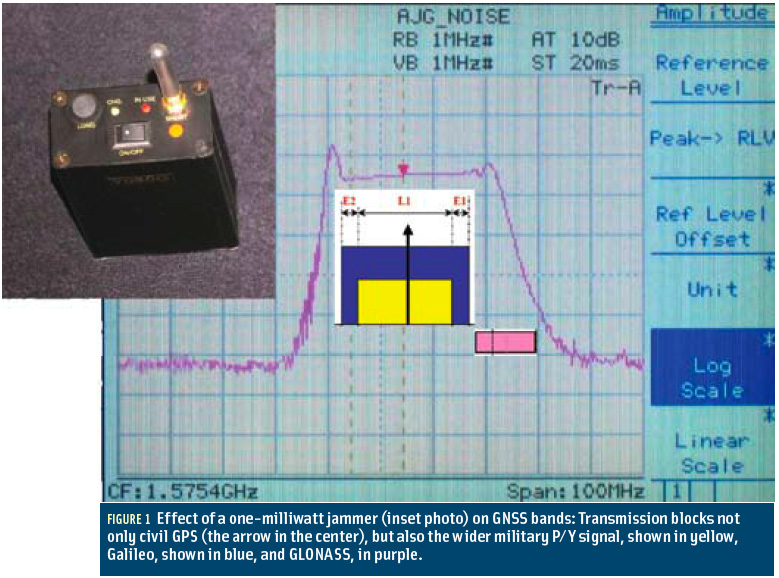

Another factor encouraging cooperation is the widening recognition that all GNSS systems face common threats, whether manmade (interference, jamming, and spoofing), natural (atmospheric phenomena), or the laws of physics (such as the cumulative effects of radiated energy in the finite RF bands in which GNSS signals operate).

Over the years, cooperative efforts have taken the form of bilateral and multilateral exchanges, often in the context of organizations such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO, which began drafting GNSS procedures nearly 20 years ago) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU, another UN-affiliated organization responsible for coordinating radio spectrum).

The emergence of the International Committee on GNSS (ICG), organized in 2005 under the auspices of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs and formally established a year later, has played an increasingly important role, with the aid of its Providers Forum and four working groups.

A founding principle of the ICG is to encourage cooperation among the various GNSSes. An ICG working group on compatibility and interoperability cochaired by Russia and the United States has been particularly active.

Annual meetings have proven increasingly informative and productive, encouraging participants to adopt a posture (if not always the substance) of promoting interoperability. This year the ICG published a 60-page report presenting the current status and plans of the GNSS providers.

The prevailing policy statement on GPS — specifically, a 2004 national security policy directive on space-based positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) — reflects an explicit effort to assert the primacy of the U.S. system.

Nonetheless, in recent years U.S. officials responsible for GPS policy and management, both civil and ever more often military as well, have pursued a more even-handed course in dealing with other GNSS systems. An evolution can be clearly seen in the agreements listed in the National Space-Based PNT Coordination Office website’s section on International Cooperation.

This change in attitude towards other GNSS providers may have reached its most forward position in the new National Space Policy announced in June. Five paragraphs on space-based PNT systems included the directive that “foreign positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) services may be used to augment and strengthen the resiliency of GPS."

Later in the year, the Obama administration made a concerted offer to open bilateral talks with China on GNSS, something that had been ruled out under President George W. Bush.

One tangible effort to achieve interoperability, advocated by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and backed by the ICG, is an Asia Multi-GNSS Demonstration Project that seeks to develop user equipment and applications that incorporate multiple GNSS systems and technologies.