Efforts to set aviation standards for larger unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have fallen behind schedule, threatening essential funding for related tests and possibly complicating an Air Force program that needs the standards to make technology choices.

The schedule is slipping because initial estimates of the work involved in setting the standards for detect-and-avoid (DAA) technology did not fully capture the complexity and extent of the effort necessary. DAA technology is intended to

Efforts to set aviation standards for larger unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have fallen behind schedule, threatening essential funding for related tests and possibly complicating an Air Force program that needs the standards to make technology choices.

The schedule is slipping because initial estimates of the work involved in setting the standards for detect-and-avoid (DAA) technology did not fully capture the complexity and extent of the effort necessary. DAA technology is intended to

prevent collisions with aircraft that don’t have a pilot onboard to spot potential hazards.

“We thought we had a 10 lb. sack,” said Paul Schaeffer, co-chair of RTCA Inc. Working Group 1 (WG1), the standards design panel tackling the problem. “We tried to put 10 pounds of stuff in it — but we had 12 pounds of stuff. We have to redefine the sack.”

The work is being coordinated by RTCA, a nearly 80-year-old nonprofit association whose volunteer members meet and develop a consensus on standards for aviation equipment and procedures. If the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) adopts their recommendations, they become the minimum requirements for aviation systems and day-to-day operations.

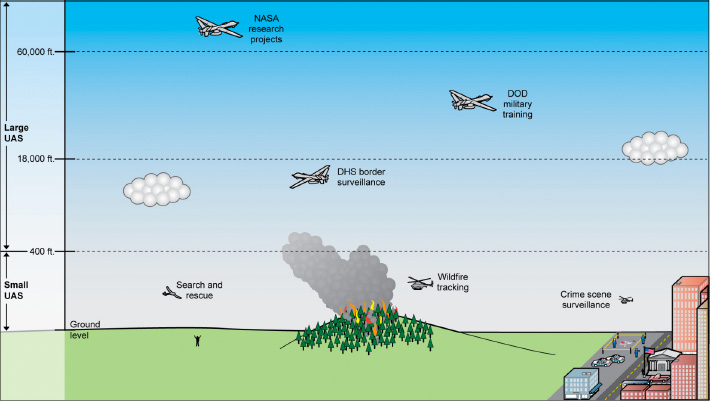

The working group is part of Special Committee 228 (SC-228), which is tasked with developing the DAA Minimum Operational Performance Standards or MOPS. The committee’s initial emphasis is on civil unmanned aircraft equipped to operate in Class A airspace under instrument flight rules (IFR). The operational environment for these MOPS is the transitioning of a UAV to and from Class A or special use airspace, traversing airspace Class D and E, and perhaps Class G airspace. (For details on classes, see this FAA manual.) A second phase of MOPS development would address DAA equipment to support extended UAS operations in Class D, E, and perhaps G, airspace.

Schaeffer said the group’s leadership made their best guess on the time needed to complete the work and took a reasonable risk — but the June 2016 deadline they set out now needs to be adjusted. The work should not require more than an additional year, he said.

“The bottom line is that we established what the goals were . . . without knowledge of the details,” Schaeffer, told Inside GNSS. “We established a scope and a schedule from a top-down position and the work we’re doing here is bottoms-up. So, as you build that bottoms-up network of activities that must be put together, it often turns out that the schedule that’s achievable is not the schedule that was desired.”

The schedule slip, however, will put critical testing resources at risk, Jim Williams, the manager of FAA’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Integration Office, said during an SC-228 meeting on November 21. The FAA, the Department of Defense, and NASA are working together to integrate UAS into the national airspace. NASA has agreed to do the testing necessary to vet the DAA standards. But if the upfront work needed to craft the standards and configure the tests is delayed, the program could end before the tests can be completed.

The vast majority of the testing should be completed by the end of September 2016 when the NASA program closes, said SC-228 co-chair George Ligler, although he acknowledged some of the tests may not finished. The group would prioritize the tests, he said, and work to find ways to push the scheduled to left.

“I think the key thing here,” said Liger, “is that we take a reality-based approach.”

Although DAA systems are a key element in integrating all kinds of unmanned aerial systems (UAS), the working group is specifically tasked with developing standards for larger UAS. While rules for UAS weighing 55 pounds or less are expected to be released this year and completed in the next couple of years, the UASs SC-228 is supporting are unlikely to be integrated into the airspace until some years later. Therefore, a delay in the working group’s efforts presumably would not necessarily delay commercial operations.

The delay and loss of testing resources, however, could affect the Department of Defense. The Pentagon has to make a decision on detect-and-avoid capability in fiscal year 2018, said an expert, who spoke on condition of anonymity to be able to discuss the issue freely. Military decision-makers need the standards to know how to choose among possible technologies.

No further details on the military program or programs involved were available by press time.

“There is a spectrum of possible ways” to deal with the potential loss of NASA funding and ease the crunch, said Schaeffer. Industry or the Pentagon could support the rest of the testing or it might be possible to reduce the amount of flight testing needed by relying more on modeling and simulation.

Both Schaeffer and Ligler praised the level of work being done by the members of Working Group 1.

“The really good news is that we’re seeing the unity of purpose and a complexity of activity within the DAA working group that I’d hoped to see. It’s really excellent’” said Liger. “So my level of confidence that they’re going to produce excellent mops is quite high.”