Although delayed for a year for lack of funding — and delayed yet again by the government shutdown — research to help set GPS-protecting interference standards appears poised to get underway.

The ABC or Adjacent-Band Compatibility Assessment is part of a broad plan to draft spectrum interference standards covering all GPS civil receivers. The approach would give potential users of frequencies neighboring the GPS band clear limits so they can test and plan accordingly.

Although delayed for a year for lack of funding — and delayed yet again by the government shutdown — research to help set GPS-protecting interference standards appears poised to get underway.

The ABC or Adjacent-Band Compatibility Assessment is part of a broad plan to draft spectrum interference standards covering all GPS civil receivers. The approach would give potential users of frequencies neighboring the GPS band clear limits so they can test and plan accordingly.

The idea emerged after the Virginia firm LightSquared declared bankruptcy after tests showed its plan to repurpose frequencies near the GPS band for wireless broadband would overload many GPS receivers and was incompatible with several safety-of-flight systems.

The National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Executive Committee proposed drafting the standards last January when it reported on the outcome of the LightSquared tests. In addition to the financial hit suffered by LightSquared, the test results were a setback for the Obama Administration, which promised to find 500 MHz for new broadband services. Political pressure has been steadily building to find a way to get more out of the overcrowded spectrum.

One concept getting increasing attention is Harm Claim Thresholds (HCT) — a proposal for expanding the use of frequencies by mandating that receivers be built to withstand a predetermined level of interference. Only if that level is exceeded can harm be claimed and the owners of the receivers seek changes in the way an adjacent band is being used.

This approach would put the onus on receiver manufacturers to find solutions without actually setting receiver standards — which are widely seen as limiting innovation. Using HCTs was proposed early this year by the Federal Communications Commission’s Technical Advisory Council (TAC), which recently suggested a pilot program to test the idea.

The ABC’s of GNSS

The ABC Assessment, a counterpoint to the HCT approach that focuses on setting limits on the emissions from users of a band, was proposed a year ago but has been in limbo pending funding. Although another approval still may be needed, the immediate financial challenge appears to have been met.

“We have some resources to proceed,” Karen Van Dyke, the director of the Positioning, Navigation and Timing Program Research and Innovative Technology Administration within the U.S. Department of Transportation told a September meeting of the Civil GPS Service Interface Committee (CGSIC).

During the ABC study researchers will attempt to identify receivers and receiver sensitivities as well as “define what we expect to operate in the adjacent bands so we can conduct some level of new testing,” said Van Dyke, who is also chair of the CGSIC. It’s an “an enormous effort to undertake,” she added.

“The overall scope (of the study) is huge,” confirmed the MITRE Corporation’s Chris Hegarty, who co-chairs RTCA’s Special Committee 159. SC-159 handles issues involving the Global Positioning System and is slated to undertake part of the research. “[The] overall scope is to implement this plan to protect all civilian GPS applications. So, the [Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)] piece of it is just really one small part — which would be looking at certified civil aviation receivers. And the FAA plans to lean on RTCA to help with that bit.”

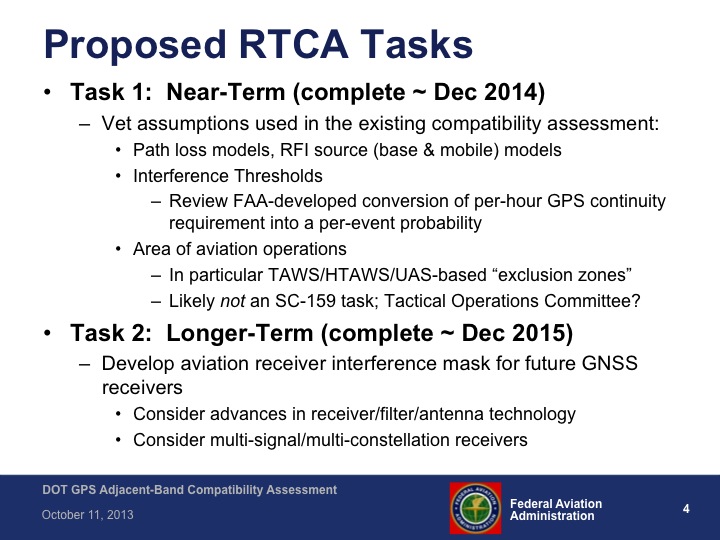

The work will be divided into two sets of tasks with RCTA’s work on the first task targeted for completion by the end of next year, according to charts reviewed at an SC-159 meeting on October 11 in Washington.

“Step 1 is basically protecting all the existing receivers that are used for civilian applications,” said Hegarty, “and then Step 2 is looking into the future at what receivers might evolve into.”

The second step, which is expected to take two years, will assess the interference risk when receivers are incorporating all the new signals from the GNSS systems that are now emerging — a point at which some equipment might require less protection.

“There are some opportunities for equipment to get a little bit better in terms of . . . adjacent band compatibility, but there is also . . . the possibility that equipment could get worse in terms of adjacent band compatibility because they are opening up to more frequencies from GNSS systems,” Hegarty explained.

The challenge of evaluating the risk to all present-day and future receivers will require more resources down the road — some of which may come from receiver manufacturers.

“While we have some resources available,” Van Dyke told attendees, “it is not nearly enough for what that is going to entail — so we’re going to look from support from industry.”

The near-term challenge, however, is just getting off the ground. The October 11 meeting of SC-159 was an informal one because, under the rules of the Federal Advisory Committee Act, the committee needed its designated federal employee present for a full, vote-taking plenary session — and that person had been furloughed.

Fortunately, said Hegarty, the study need not wait until the next SC-159 meeting in March for approval. A formal letter from the FAA will be enough to get started.