Michael Sanjume, deputy chief of the GPS Directorate User Equipment Division

Michael Sanjume, deputy chief of the GPS Directorate User Equipment DivisionThe Air Force may dial back plans to accelerate its military receiver program, possibly reversing an earlier decision to combine development and production steps as a way to meet a congressional procurement deadline.

The Air Force may dial back plans to accelerate its military receiver program, possibly reversing an earlier decision to combine development and production steps as a way to meet a congressional procurement deadline.

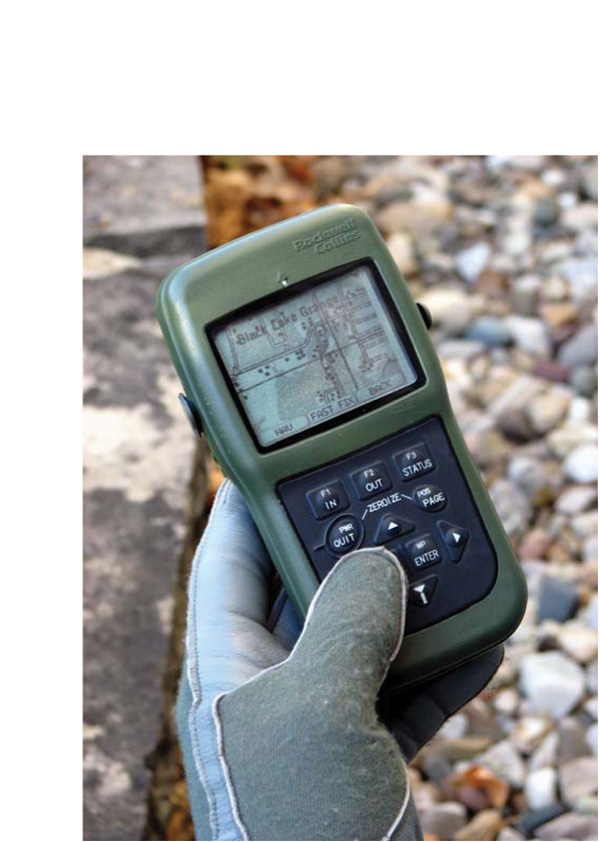

The Military GPS User Equipment (MGUE) program is developing next-generation GPS receiver cards that can be swapped out, one-for-one, for the current receivers in a wide variety of existing military equipment. The new receivers will be able to tap the more powerful M-code signal, which is not only more secure and flexible but spectrally separated from the L1 and L2 civil signals — a distinct advantage in a jamming environment.

The receivers are being developed by the GPS Directorate, which has been scrambling to meet a congressional mandate that all GPS receivers bought in fiscal year 2018 and thereafter be M-code capable. That deadline helped drive a 2014 decision to condense the development and manufacturing process, skipping as a result the critical design review (CRD) — usually a key step in any development contract.

Normally, new receivers would go through an extensive step-by-step process of systems engineering, development, and design. Officials would then mature the manufacturing line, testing it with low production runs — then testing it further until approval was finally granted to begin full production.

But the production lines to be used for the MGUE cards are same ones producing the Selective Availability Anti-spoofing Module or SAASM cards. Given that experience, the Air Force decided it could use an abbreviated approach, said Lt. Col. James Wilson, program manager for the Military GPS User Equipment (MGUE) program, in an interview with Inside GNSS last year. The three vendors on the project — Rockwell, L3/Interstate Electronics Corporation, and Raytheon — were to begin delivering cards for evaluation this summer with a decision to be made in September about how to proceed.

Those cards are now “showing up on our docks literally every week,” said Michael Sanjume, deputy chief of the GPS Directorate’s User Equipment Division. Two different types of receivers, one for ground equipment such as radios and one for air/marine applications, began arriving in July and deliveries will continue into September.

“For us the proof is in the pudding when you deliver hardware. So we’re very excited that we’ve had these to start our initial testing,” Sanjume said.

GAO Report Raises Questions

Although these initial deliveries are on schedule, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report September 9 that calls the accelerated approach into question. GAO said the program has risks that were not addressed during early design work, risks that would “typically be revisited” during the now nonexistent CDR phase.

The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for System Engineering, for example, identified some specific areas of concern in April, the report said. Certain security and cybersecurity design details had been deferred to a security verification review that was not scheduled to finish until late summer/early fall 2015. Early design work on the interfaces with the lead platforms chosen by each of the services may not have been rigorous enough “to account for implementing those designs across various operating environments.”

“The Undersecretary’s office also pointed out,” wrote GAO, “that the refinement of security countermeasures may result in later design changes.”

In addition to these points, the GAO highlighted a disagreement between the Army and the Directorate over whether the MGUE design actually meets the Army’s operational requirements, including the Army’s assertion that the GPS Directorate unilaterally edited a key requirements document over the Army’s “significant objection.” The problem, which involves average maximum versus instantaneous power limits, could force the services to do additional development work to integrate the cards into their equipment.

Questions were also raised about the scope and usefulness of both early and planned MGUE testing — testing that won’t be fully complete until sometime in 2019, well after the congressional M-code-only purchase mandate kicks in. The Army, for example, said that “fit check” tests conducted earlier this year showed the Defense Advanced GPS Receiver (DAGR) D3, the lead platform chosen by the Army, is unable to provide sufficient power to two of the three MGUE contractors’ ground receiver cards, according to the report.

Search for Plan B

Sanjume said the Directorate and the Office of the Secretary of Defense were discussing the “actual maturity of the program, both technically and programmatically,” as well as the best approach to take for the next phase.

“We had originally planned on a combined production and development decision; and there might be basically a split and there might be a bit of a change to our strategy,” he said.

One possibility, Sanjume explained, is to change from going into production right after demonstrating the technology.

“In breaking it apart,” he said, there “would be a development gate and then a gate into actual production where you could buy articles that would actually go into operations.

Sanjume said his team believes development is complete as the result of the predecessor MUE program and that MGUE is “a fairly mature program.”

“We will get further guidance,” he told Inside GNSS, “from the Department [of Defense] on what will actually be decided this fall.”

While they wait for the decision Sanjume’s team continues to work with the services on integration plans and risk reduction activities, such as plugging the cards into equipment to see if they actually fit. The Directorate is also setting up a security certification and compatibility certification process for all MGUE receivers.

“So that will be something that will be part of our responsibility in the future,” said Sanjume, “and that is a bit of a change. We’ve been working very closely with all the different services to establish the program protection profiles, which are essentially the security requirements that we will set for each of the applications. We have made good progress on those and we are close to finalizing all of them.”

The compatibility and security certifications pose a challenge beyond the tasks themselves. They are making it harder for the Air Force to expand the vendor base for that cards as it had hoped.

To help address that, Sanjume said the directorate was exploring concepts for providing some of the intellectual property for the cryptography and security processing as a way to lower the cost of entry for new vendors, especially small businesses.

“We definitely have heard interest from industry on that front,” said Sanjume, “and we are looking at ways that we can basically enable it. We also believe that it’s one of the key things that we can do to foster more innovation into user equipment and faster cycle times — which I think is another strong theme of acquisition reform.

So we’re absolutely very interested in this area.”

The MGUE program will undoubtedly be an area of special interest to Col. Steve Whitney, who in July became director of the Global Positioning Systems Directorate in the Space and Missile Systems Center at Los Angeles Air Force Base, California. For the two years before his appointment, Whitnes served as the Senior Materiel Leader, Global Positioning System User Equipment Division, in the GPS directorate.