LightSquared told a congressional committee today (September 8, 2011) that it would limit the on-the-ground power of its signals to avoid overpowering GPS receivers, which use frequencies next door that the company proposes to have rezoned for its high-powered wireless broadband network.

LightSquared told a congressional committee today (September 8, 2011) that it would limit the on-the-ground power of its signals to avoid overpowering GPS receivers, which use frequencies next door that the company proposes to have rezoned for its high-powered wireless broadband network.

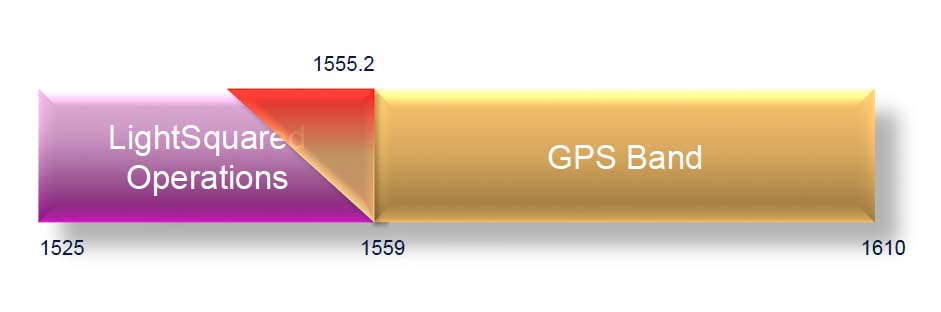

Tests this year <https://www.insidegnss.com/node/2678> showed that broadcasts from the proposed wireless broadband network, given conditional approval by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) early this year <https://www.insidegnss.com/node/2471>, would overload a wide range of GPS receivers.

Officials from several federal departments said during the hearing that GPS receivers used by their agencies — even those on satellites — would be adversely affected, undermining their departments’ abilities to issue accurate hurricane warnings, protect those battling wild fires, forecast the week’s weather, predict flooding and locate distressed sailors.

“I could not say with confidence today that we could fulfill our mission, Mary Glackin, deputy under secretary at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told the House Committee on Science Space and Technology.

Even half a mile away the LightSquared signal is 500 billion times more powerful than the GPS signal, explained Tony Russo, director of the National Coordination Office for Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing.

"If GPS is a teaspoon of water,” he said, “LightSquared is Niagara Falls.”

Russo told the committee that it was not clear if a technical fix was possible.

"Technical experts are split as to whether it is even feasible that we could put a filter in that was both strong enough to knock out the LightSquared signal and still allow us to do our mission.”

If a fix was found, the cost to replace receivers could run into the hundreds of millions of dollars. David Applegate, associate director for natural hazards at the U.S. Geological Survey said his agency estimated it had invested $100 million in technology so far and it would cost $500 million to replace its receivers.

The responsibility for the problem lies with the GPS community, asserted Jeff Carlisle, LightSquared’s executive vice president for regulatory affairs and public policy, suggesting that part of the fix lay in new GPS receivers. The community had had plenty of time to prepare for the introduction of the LS network, Carlisle said.

“If you are talking about public safety, Rep. Jerry McNerney, D-Calif., told Carlisle “that is a losing argument.”

Each of the government officials stressed that the interference tests done to date had been based on the network as originally proposed at the end of 2010. Shortly before testing ended this summer, LightSquared said it would lower its broadcast power and shift its operations for an unspecified period to the lower 10 megahertz of the total 20 megahertz allocated some years before for its satellite-to-ground operations. The system as now proposed would effectively reallocate the space-to-ground spectrum for use primarily by a terrestrial system with up to 40,000 ground stations.

Federal officials emphasized that they needed to test the new configuration.

Carlisle told the committee that to address the overload problem LightSquared had told the FCC the day before (September 7, 2011) that it would limit its on-the-ground power to no more than -30dBm at the start of the systems’ deployment. They would increase the power to -27dBm by January 1, 2015, and -24dBm by January 1, 2017.

The firm said it would also commit to providing a long-term, stable satellite signal for MSS-provided GPS satellite-based augmentation services. LightSquared provides such signals now and the final fate of those signals has been of concern to precision GPS users.

“It would be a limit on what power would be received at any point,” Russo told Inside GNSS. “They would have to adjust the power they put out in order to do that . . . adjust their antenna angle and all this other stuff.”

This approach would address concerns about the propagation model, the power threshold, and the issue of aggregate effects from multiple towers,

"If the power is low enough, that fixes the problem,” Russo said. “I don’t know if their number is low enough.”

“I still want to test,” added Russo. “Anything they do I still want to test. But it is a creative proposal, and we’ll seriously consider it.”