With more testing on the horizon and a potentially alarming homeland security report about to be released, LightSquared’s efforts to begin work on its proposed wireless broadband service are stuck in the procedural mud.

The delays, which are never good for a commercial company, are piling up just as the firm’s coffers are thinning and need to be replenished with a new round of fund raising.

With more testing on the horizon and a potentially alarming homeland security report about to be released, LightSquared’s efforts to begin work on its proposed wireless broadband service are stuck in the procedural mud.

The delays, which are never good for a commercial company, are piling up just as the firm’s coffers are thinning and need to be replenished with a new round of fund raising.

LightSquared wants the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to give it the go-ahead to build a terrestrial 4G wireless broadband network, using spectrum originally allocated for satellite-to-ground communications. They have permission, of a sort — a January 26 FCC order and authorization conditioned on the service not interfering with GPS L1 signals located in the adjacent band of frequencies.

Tests this summer, however, showed that signals from LightSquared’s high-power ground stations — the firm plans to build up to 40,000 of them — would overload the vast majority of GPS receivers and create additional harmonic intermodulation products that would add to the interference. More tests are either underway or proposed on new filters and other measures aimed at reducing interference to GPS receivers.

Although the GPS community is skeptical and frustrated by months of expensive, rush-rush testing, LightSquared is proceeding on the assumption that some sort of fix will be found. If and when it is, company officials are telling Washington policy makers that GPS receiver manufacturers should foot most of the bill for putting the fix in place, not LightSquared.

Testing, Testing . . .

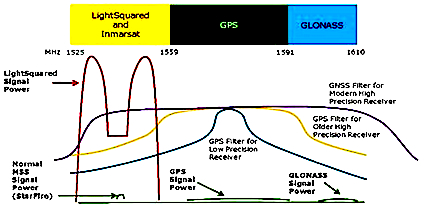

When originally announced the LightSquared project planned to use 10 megahertz of spectrum at 1526–1536 MHz and 10 megahertz more at 1545-1555 MHz, which is immediately below the GPS band.

After testing over the summer showed that LightSquared signals in the upper 10-megahertz band were devastating to the vast majority of brands and types of GPS receivers, LightSquared offered to forego using that part of the spectrum — for a while — and lower the received power of ground transmitters.

Since then the firm has been working hard to find interference fixes.

In September it announced the development of a new filter and several other devices that, they say, will address the particularly thorny problem of interference to high-precision GPS receivers.

Though promising, the new technology has not been independently tested. In fact, very little has actually been resolved regarding any of the areas of interference.

As of early November:

- Testing was still underway on cell phones.

- The results of just-completed tests on general location and navigation equipment were still being analyzed.

- The military was set for a new round of classified tests.

- The National Telecommunications and Information Administration, which manages the use of frequencies by the federal government, had “left the door open” for more testing for timing receivers, according to LightSquared.

- Testing was expected to begin in December on several possible solutions to the lower 10-megahertz interference to high-precision GPS receivers.

- No tests were planned as yet on LightSquared handsets, another possible source of interference, because handsets were still unavailable. Handsets will transmit in bands above GPS L1.

The aviation community, meanwhile, was in discussions with LightSquared about its receivers. Widely installed in commercial and private aircraft and rigorously certified, aviation receivers pose a particular problem for company’s plans. If they have to be replaced, the certification process alone would take years, be terribly expensive, and utterly unavoidable.

A lower 10-megahertz plan might prove workable for aviation users, and the company is trying to hammer out a solution with the aviation community to avoid triggering recertification.

So Much Fun the First Time . . .

A significant problem for many users, however, is the lack of certainty about whether any solution arrived at now would be permanent.

Though the company has offered to focus on using its lower band to kick things off, it has steadfastly refused to officially forego use of its upper 10 megahertz of spectrum. The company has leased the spectrum from Inmarsat for 99 years, said LightSquared Executive Vice President Martin Harriman, and has 94 more years to find a technical fix for the interference issues.

“I think it is astonishing that we are being asked to walk away from that spectrum by the GPS community,” he said.

To eliminate that uncertainty, the Coalition to Save Our GPS, a leading advocacy group opposing the LightSquared effort, asked the FCC in an ex parte filing on November 8 to “promptly rule” that LightSquared not be permitted to pursue high-powered terrestrial operations in the upper 10 megahertz. (See the related news article in this issue.)

There may, however, be a deal in the works.

Reading between the lines it seems that LightSquared might be open to selling the upper 10 megahertz and is, in fact, talking with stakeholders about that band.

“Spectrum is very valuable,” said Harriman, who is the firm’s executive vice-president for ecosystem development and satellite business. “The GPS Coalition has taken a stab at estimating what the value is. We’re running into billions of dollars for that spectrum. We’re working very closely with agencies. We are working very closely with the industry, and we are trying to work a way through that will make us compatible with the industry.”

Jeffrey Carlisle, LightSquared’s executive vice president of regulatory affairs and public policy, acknowledged the concerns about the upper 10 megahertz and confirmed discussions were underway.

“We are going to continue to talk to the stake holders about [the upper 10 MHz],” he said.

Raising Cash

LightSquared might be particularly open to selling the upper 10 megahertz just now. Sources have told Inside GNSS that the firm needs new funding and is facing a skeptical debt market.

Independent sources in the financial community confirmed a Reuters news report that LightSquared’s debt is now being traded at 50 cents on the dollar. That is down from the 70 cents on the dollars seen earlier this year — but an improvement from the weeks just after General William L. Shelton, commander of U.S. Air Force Space Command told members of Congress that tests showed “the LightSquared network would effectively jam vital GPS receivers.” At that point, the LightSquared debt was selling for 40 cents on the dollar, said one source, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

LightSquared, which is a privately held firm, declined to comment on the discounts to its debt.

“They are in a lot of trouble right now,” the finance expert told Inside GNSS. “They need to raise cash.”

Though an analysis by TMF Associates’ telecom expert Tim Farra indicates LightSquared may have enough money to carry it into 2012, the source explained the firm must raise money well in advance of its budgeted needs — and that may not be easy.

The markets seem to be assuming that a solution will be found for the lower 10-megahertz problem, the source said, but it is not clear when such a solution can be brought to market — and that is causing concern.

Members of the finance and investment community are monitoring the issue closely and have been spotted at the LightSquared session at the Institute of Navigation meeting in Portland this fall and at least one congressional hearing, and at the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Advisory Board meeting in Washington on November 9.

No FCC funds

What appeared to be one possible source of money is now off the table — at least as a direct source for LightSquared: the FCC itself.

On October 27, the agency approved a major reorganization of the way it handles the Universal Service Fund. The fund, fed by small fees found on every phone bill, was earmarked for programs to provide phone service for everyone. Now some of that money will go to supporting the development of broadband across the country.

The FCC is dedicating $100 million of the revamped Universal Service Fund specifically to wireless networks through a new Mobility Fund. That money, however, is not available to LightSquared, FCC officials told Inside GNSS, because of company’s structure as a wireless broadband wholesaler.

LightSquared customers could apply for the one-time subsidy, they said, which could indirectly benefit the company — but LightSquared itself is apparently not eligible for direct aid.

Government Analysis Continues

Given the expanded testing ahead, the FCC clearly will not be able to make a decision on LightSquared’s request for weeks, maybe months. The delay means that they, and other policy makers, will be able to take into consideration a new report from the Department of Homeland Security.

DHS has been working for over a year to assess the impact of inference on the nation’s GPS-linked infrastructure and what it would mean to critical services — specifically communications, emergency services, energy, and transportation systems. Under the FCC’s original, turbo-charged testing/decision-making schedule for LightSquared, the report would have come too late to be a factor.

In fact, DHS had said last spring that its assessment would not specifically address interference from LightSquared. They were looking at the “potential impacts to critical infrastructure from interference — regardless of its source — that disrupts the ability of critical infrastructure to use GPS-derived PNT information to support their missions.”

LightSquared is, however, included in the final report, albeit indirectly, said Brandon Wales, director of DHS’s Homeland Infrastructure Threat & Risk Analysis Center.

“We dealt with [LightSquared] through the sections that talked about bandwidth crowding – what happens if frequencies get too close to the GPS spectrum and impact it,” he told the November meeting of the PNT advisory board.

“We also looked at several of the potential disruption scenarios — at a kind of consistent disruption of the GPS signal from a high-powered source, which in many cases would be similar to a powerful signal operating very close to the GPS spectrum, causing that kind of consistent disruption — similar to a powerful jammer over a broad area.”

Now in the hands of the PNT Executive Committee and under final federal review, the report should be released in January. A declassified version of the report, which is entitled the “National Risk Estimate: Risks to U.S. Critical Infrastructure from Global Positioning System Disruptions,” should be available, said Wales.

PNT Weighs In

The advisory board meeting was awash in discussions about LightSquared, with the main event being a briefing by Javad Ashjaee, CEO of JAVAD GNSS, and a panel of GPS and LightSquared representatives. Board staff estimated that 200–250 people attended that session — many of them from LightSquared, whose headquarters office is in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Reston, Virginia.

The board vigorously debated about how to advise the PNT Executive Committee regarding LightSquared when the ExCom meets in December. There were two points of view centered on whether or not it made sense to proceed when disposition of the upper 10 megahertz was still up in the air.

“If we are to pursue any further action on LightSquared, such as a technical validation of any proposed solution, someone needs to define what the end state is for how LightSquared will operate,” said James Geringer, elected temporary vice-chair of the advisory board and director of policy and public sector strategies at the ESRI. “Until the end status is defined the best we can do is to observe . . . the potential impacts on the broad community of GPS users.”

Geringer added, ‘The other point of view is, ‘Couldn’t we go ahead and do the independent validation using the lower band only?’ I think there is a lot of hesitation by most of the committee members that we shouldn’t even go that far, because that implies at least a ‘two-step’” series of changes to adapt for LightSquared.

Absent from the LightSquared debate were the board’s vice-chairman Brad Parkinson, and others who left the meeting, they said, on advice of legal counsel to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Although the PNT Board members are vetted extensively under rules that apply to all federal advisory boards, LightSquared had singled out Parkinson, the first U.S. Air Force director of the GPS program, as being biased against the broadband company. He is on the board of Trimble — a GPS manufacturer and leading LightSquared opponent.

Among others who left during the LightSquared presentation and/or subsequent discussions were Dean Brenner, Qualcomm; Joseph Burns, United Airlines; Ann Ciganer, U.S. GPS Industry Council; Ronald Hatch, NavCom Technology (John Deere), and Timothy Murphy, the Boeing Company.

That did not stop the board from taking on the issue of GPS receiver standards — which had arisen after LightSquared wrote a letter to the FCC pointing to what they said was a government standard for receivers and blaming interference problems on the failure of GPS receiver manufacturers to follow it.

“The committee has said there are two different issues here [regarding a GPS receiver standard],” said Geringer. “One is ‘Should there be a standard of any kind for receivers? The second is what LS has asserted as a standard, is very explicitly stated not to be a standard.”

LightSquared had posited that the Global Positioning System Standard Positioning Service (GPS SPS) Performance Standard published in September 2008 — which sets forth what users can expect from the GPS satellite signals in space — incorporates receiver standards. The document is available here.

In fact the same section of document cited by LightSquared states, at the beginning, that the “representative receiver characteristics are used to provide a framework for defining the SPS performance standards. They are not intended to impose any minimum requirements on receiver manufacturers or integrators, although they are necessary attributes to achieve the SPS performance described in this document.”

You Got the Bill?

LightSquared may be pressing on the issue of receiver standards because it goes to the question of who should pay for any changes or retrofits necessary to accommodate their system.

“Users should not be required to pay a dime for this,” said Jeffrey Carlisle, LightSquared’s executive vice president of regulatory affairs and public policy.

LightSquared asserts that the GPS community should have known from prior FCC proceedings that it was building a terrestrial network and adapted their receivers accordingly. GPS firms and government agencies insist that the LightSquared network is a new and unanticipated rezoning of the frequencies next to theirs and should not be allowed.

The Coalition to Save Our GPS has countered with similar arguments to establish the primacy of GPS signal designs, including most recently a section of their November 8 FCC filing to eliminate the upper 10-megahertz band from consideration.

In the filing the Coalition argues that design of the modernized military signal (M-code), published more than a decade ago, by itself should prevent use of the upper band by LightSquared.

In a clever concession that splits the interests of federal GPS users from those of the commercial community, LightSquared has already offered to pay to replace or retrofit the government’s high precision receivers.

“Who pays for the commercial precision receivers — which is what this all boils down to at the end of the day. That’s a commercial issue — something that the federal government doesn’t have to decide,” said Carlisle.

“It’s still a very open question as to whether the filter devices being touted as ‘solutions’ will work,” said the Coalition in a statement e-mailed to Inside GNSS. “But if testing does confirm their viability, it’s preposterous to think that either the users or the manufacturers of existing GPS devices should have to bear the burden of paying for the retrofitting or replacement of those devices.

“The FCC has consistently held that transition costs must be borne by the party proposing a new use, not prior spectrum users who acted in good faith reliance on prior decisions, as GPS users and the industry did here.”