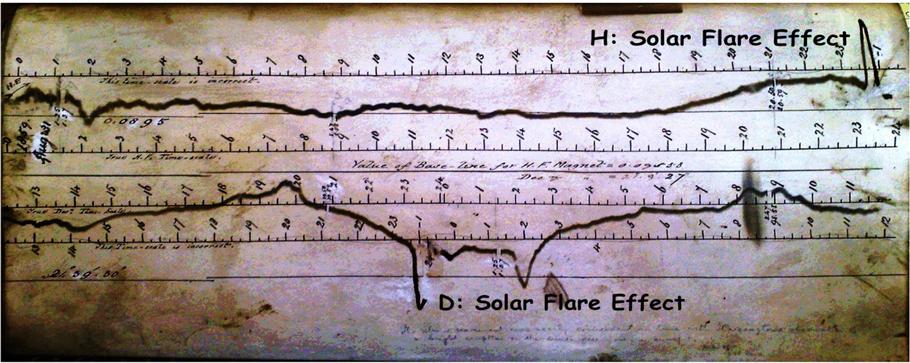

One of 12 magnetograms recorded at Greenwich Observatory during the Great Geomagnetic Storm of 1859.

One of 12 magnetograms recorded at Greenwich Observatory during the Great Geomagnetic Storm of 1859.Good thing the global navigation satellite systems hadn’t been invented yet in 1859. From August 27 to September 7 the first observation of a solar flare and the most powerful geomagnetic storm in history happened, and it shook everybody up.

The solar coronal mass ejection was so powerful, particles traveled from Sun to Earth in 18 hours. the Northern Lights were visible in Cuba and Hawaii, and the Sourthern Lights in Brisbane, Australia.

Good thing the global navigation satellite systems hadn’t been invented yet in 1859. From August 27 to September 7 the first observation of a solar flare and the most powerful geomagnetic storm in history happened, and it shook everybody up.

The solar coronal mass ejection was so powerful, particles traveled from Sun to Earth in 18 hours. the Northern Lights were visible in Cuba and Hawaii, and the Sourthern Lights in Brisbane, Australia.

The world’s communication infrastructure was in its infancy, so it was mainly the electric telegraph systems of the time in Europe and North America that went haywire on September 2. Boston operators told the New York Times, “We observed the influence upon the lines at the time of commencing

business — 8 o’clock — and it continued so strong up to 9 1/2 as to

prevent any business from being done, excepting by throwing off the batteries at each end of the line and working by the atmospheric current entirely!”

Luckily, neither airflight nor satellites nor electronic bank transfers nor GPS-aided navigation nor powerlines were around to suffer from the ionospheric disturbance.

In June 2013, researchers at Lloyd’s of London

and Atmospheric and Environmental Research Inc.

used data from the the Great Geomagnetic Storm to estimate that it would cost $600 billtion to $2.6 trillion in the United States alone if it hapened today.

Observations at the time set the foundation of the study of space weather as we know it. Sunspots had been known since Galileo’s time, but two Londoners -both serious amateurs- made and confirmed the first scientific observations of a solar flare. Astronomer Richard Carrington noted in his report "two patches of intensely white and brith light broke out," and R. L Hodgson, who worked several miles away, confirmed it.

The Greenwich Observatory recorded the effects of the world’s largest magnetic storm between August 27 and September 7, 1859 and you can download a poster with all 12 magnetograms at the British Geological Survey website here.